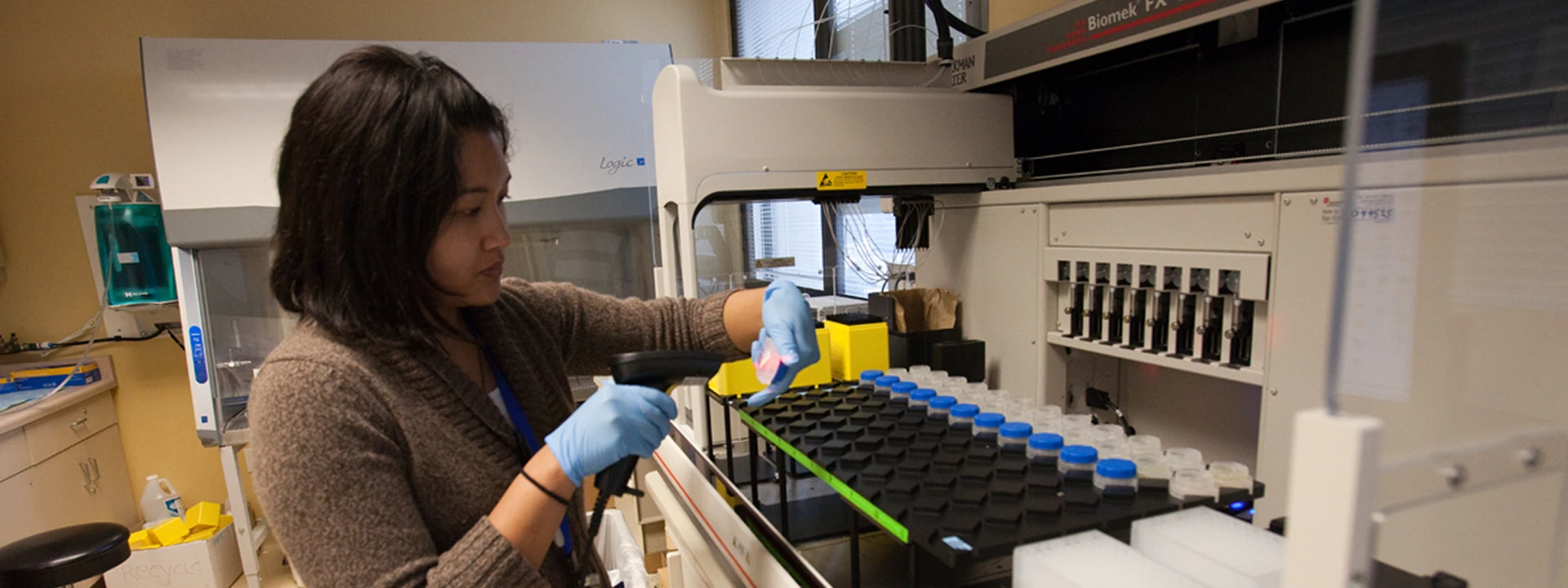

Transforming Health through research

Kaiser Permanente Division of Research

Publications and Studies

Tools for Clinicians and Collaborators

We provide support and direction to clinician researchers and external partners with all aspects of collaborating, planning, and conducting clinical research within Kaiser Permanente Northern California.

Our Scientists

Laurel A. Habel , PhD

Research interests include the etiology and progression of cancer.

Read Scientist’s BioParticipate in a Study

Visit the KP Study Search website to find out how participating in research studies benefits participants and society at large, and learn which studies are looking for participants.