Kaiser Permanente researchers find commonly used lab test could potentially affect diabetes diagnoses and lead to incorrect assessments of health disparities in diabetes control

A blood test commonly used to diagnose and manage diabetes is more frequently inaccurate in Black patients, new Kaiser Permanente research shows.

The study, published in Diabetes Technology and Therapeutics, is one of the largest to show that the hemoglobin A1c (A1C) lab test — the most frequently used test to diagnose diabetes and monitor its control —often incorrectly estimates average blood sugar levels in Black patients.

“Our study — which is one of the first to compare Black and white patients to patients of other racial and ethnic groups — adds to the evidence that A1C tests more frequently fail to accurately reflect average blood sugar levels in Black patients than among other racial and ethnic groups and that should be taken into account when diagnosing or treating patients with diabetes,” said lead author Andrew J. Karter, PhD, a research scientist at the Kaiser Permanente Northern California Division of Research.

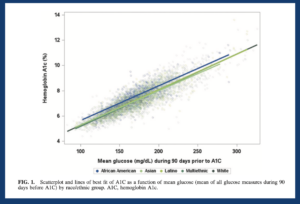

The retrospective study included 1,788 Kaiser Permanente Northern California (KPNC) patients with diabetes who used a continuous glucose monitoring device between 2016 and 2021 and also had A1C blood tests at a Kaiser lab. The researchers compared the results of the patients’ A1C blood tests to their average blood sugar levels recorded on their continuous glucose monitor over the previous 3 months.

The study found that the average A1C was .33 percentage points higher among Black patients relative to white patients with the same average blood sugar levels. There were no significant differences in A1C results for Asians, Latinos, and multiethnic patients.

“That percentage — .33 — may not seem like a lot,” said Karter. “But it can be enough to push a patient’s diagnosis of pre-diabetes to one of diabetes and to start them on treatment or, in other cases, to increase or change a person’s diabetes medications.”

Although the study found that, on average, the association between A1C and average blood sugar levels was clearly different in Black patients relative to white patients, the differences in that association between individual patients within each racial and ethnic group were much more significant than differences between racial and ethnic groups.

“There is a subset of patients across all racial and ethnic groups for whom A1C is not a good indicator of their actual average blood sugar level,” said senior author Lisa Gilliam, MD, PhD, an endocrinologist with The Permanente Medical Group and the clinical lead for the KPNC Diabetes Program. “So, while the likelihood that A1C is not reflecting actual average blood sugar levels is higher in Black patients, you can’t assume this is happening for all Black patients or that it is not happening in patients of other races or ethnicities. That’s why we need to look at each patient and determine whether A1C is or is not a good indicator of their average blood sugar levels.”

An A1C test measures the percentage of red blood cells that are bound with sugar; it does not directly measure glucose levels. This inexpensive test is widely used because it does not require fasting and the percentage of blood cells bound to sugar indicates how well patients have been managing their blood sugar levels during the previous 3 months.

“Clinically, we’ve known for some time that A1C is an imperfect measure of blood sugar control,” said Gilliam. “We regularly see patients who have an A1C level that does not match their average blood sugar levels and, in those patients, we know A1C isn’t reliable.”

This problem with the A1C test could potentially lead to inaccurate assessments of health disparities or health inequalities across racial and ethnic groups. It could also impact national health care quality assessments that use the A1C test to determine how well hospitals are managing their patients’ diabetes.

This problem with the A1C test could potentially lead to inaccurate assessments of health disparities or health inequalities across racial and ethnic groups. It could also impact national health care quality assessments that use the A1C test to determine how well hospitals are managing their patients’ diabetes.

“Social determinants of health are known to play a large part in the disparities we see in diabetes control rates between Black and white adults,” said Gilliam. “Our study does not discount that, but it does suggest that A1C more frequently incorrectly estimates blood sugar control in Black patients.”

The study was funded by the Kaiser Permanente Community Health Research Grants Program, the National Institute on Aging, and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases.

Co-authors include Melissa M. Parker, MS, and Howard H. Moffet, MPH, of the Division of Research.

# # #

About the Kaiser Permanente Division of Research

The Kaiser Permanente Division of Research conducts, publishes and disseminates epidemiologic and health services research to improve the health and medical care of Kaiser Permanente members and society at large. It seeks to understand the determinants of illness and well-being, and to improve the quality and cost-effectiveness of health care. Currently, DOR’s 600-plus staff is working on more than 450 epidemiological and health services research projects. For more information, visit divisionofresearch.kaiserpermanente.org or follow us @KPDOR.

Comments (0)