Kaiser Permanente patient registry provides unique opportunity to study likelihood of rupture

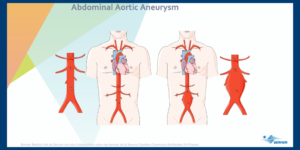

An abdominal aortic aneurysm is often referred to as “a ticking time bomb.” That’s because if the aneurysm bursts, it is likely to result in a deadly torrent of internal bleeding.

These aneurysms — bulges that develop in the abdomen in the lower part of the aorta, the largest artery in the body — usually cause no symptoms. Most people don’t know they have one until it is identified on a CT scan ordered because of another health problem. But they aren’t uncommon. In the U.S., about 200,000 people are diagnosed with an abdominal aortic aneurysm every year and about 10,000 people die after an aneurysm ruptures, making it the 15th leading cause of death.

Doctors typically don’t recommend that a patient undergo surgery until the aneurysm has grown large enough to potentially rupture. For decades, the size threshold for surgery was 5.5 cm (2.2 in) for men and 5 cm (2 in) for women. But how likely is it that an abdominal aortic aneurysm that large will actually rupture? Robert Chang, MD, a vascular surgeon at The Permanente Medical Group and a physician researcher at the Kaiser Permanente Northern California Division of Research, is the senior author of the largest-ever study to answer that question. The findings, published in July in the Journal of Vascular Surgery, are expected to influence how physicians help patients decide if they should consider surgery to remove the blockage.

Chang discussed why it was important to study the natural history of large abdominal aortic aneurysms and how the Kaiser Permanente Northern California (KPNC) health care system made it possible.

Why did you decide to conduct this study?

Chang: Abdominal aortic aneurysms are still a leading cause of death in this country, due to rupture. The way we treat them is to repair them when they get to be a certain size, but the size threshold we have used has been based on information from studies that are quite old. We believed it was important to use contemporary data to identify a patient’s risk of an aneurysm rupturing. Before our research, no one had done this.

How did you use KPNC’s electronic medical records in your research?

Chang: We have an electronic registry of 15,000 patients with abdominal aortic aneurysms that we have used for surveillance for 18 years. We use that registry to monitor our patients, but it had never been used for research purposes. It took many steps for us to figure out how to use the registry to study these patients’ outcomes. We also had to develop a natural language processing tool that could examine the medical records and figure out which imaging studies showed an abdominal aortic aneurysm and also tell us the size of the aneurysm when it was first diagnosed and how much it grew over time. It would have taken us years to look through all those records. The software could do it in just a few hours.

Chang: We have an electronic registry of 15,000 patients with abdominal aortic aneurysms that we have used for surveillance for 18 years. We use that registry to monitor our patients, but it had never been used for research purposes. It took many steps for us to figure out how to use the registry to study these patients’ outcomes. We also had to develop a natural language processing tool that could examine the medical records and figure out which imaging studies showed an abdominal aortic aneurysm and also tell us the size of the aneurysm when it was first diagnosed and how much it grew over time. It would have taken us years to look through all those records. The software could do it in just a few hours.

What did you learn?

Chang: The obvious question was: Can we figure out whether the size threshold we use based on the older studies to counsel patients about surgery still makes sense? This type of study had never been done before because no one has had access to this kind of data set. So, we looked to see if there were patients in the registry who had large aneurysms that for whatever reason were not fixed right away. And then we looked to see what happened after the aneurysm reached the threshold where we would talk to a patient about surgery. Did their aneurysm rupture? Did they go on to have surgery later? Did they die?

It turned out we had over 3,000 patients who had a large aneurysm. About 40% had one at the threshold size — 5.5 cm in men, 5 cm in women — at the first imaging study, and the other 60% had small aneurysms that grew over time. What we found was that, essentially, the incidence of rupture is lower than we thought across the board for every starting size. We also learned the risk of rupture is not cumulative. The curve is much flatter, so there isn’t this huge increase in risk of rupture if you wait longer.

What we found was that, essentially, the incidence of rupture is lower than we thought across the board for every starting size.

Is this good news for patients?

Chang: It’s realistic, more accurate news. If I have a male patient with a 5.5 cm aneurysm, I need to be able to explain the risk of it rupturing today, the risk it could rupture in the next 5 years, and the risks associated with surgery. We had thought that if you have a 5.5 cm aneurysm, you have a 5% risk for rupture at 1 year, and that the risk is cumulative, meaning in 5 years it would be 25%. Now, I use the data from our study that shows the rupture risk at 1 year is only 1.3%, which is one-fifth of what I’d have told someone in the past. And they can then compare that risk to the risks associated with having surgery.

Did you find differences between women and men?

Chang: We demonstrated that women have a different risk of abdominal aortic aneurysm rupture, and that it could actually be higher than in men. Right now, we don’t really know why. But this is something we can explore because we have so many women in our cohort. Most studies have used databases that don’t have as many women as we do.

What’s next?

Chang: The next question we are asking will be focused on the patients with small aneurysms. We want to see if we can predict who will go on to need surgery. This information would help us to conduct surveillance and, potentially, to intervene at the appropriate time to prevent a patient from experiencing a catastrophic rupture. The goal in treating aneurysms is to prevent rupture, but you also don’t want to do unnecessary surgery.

Comments (0)