Kaiser Permanente analysis finds female children could have higher likelihood of autism if their mother had a metabolic disorder early in pregnancy

A new analysis of Kaiser Permanente Northern California mothers and children adds to evidence that maternal blood sugar metabolism in pregnancy could play a role in the likelihood a child has of being diagnosed with a neurodevelopmental disorder.

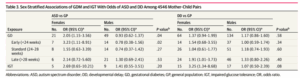

The study of 4,546 mother-child pairs did not find a significant link between gestational diabetes and risk of autism spectrum disorder or developmental delay in the children analyzed as one group. But when the researchers broke the data down by child sex and other factors, they found an elevated risk associated with gestational diabetes among girls only, and in children of both sexes whose mothers were diagnosed with gestational diabetes early in pregnancy (before 24 weeks gestation).

A separate, less serious form of metabolic disorder, known as impaired glucose intolerance, was associated with increased risk of developmental delay. The study was published in JAMA Network Open.

Maternal blood sugar metabolism is one of many health factors being studied for their potential role in children’s development of autism. These findings, while statistically significant and in a large, well-designed study, add to the evidence around the complex question of how gestational diabetes might relate to autism. But they are not intended to prompt any changes in clinical advice to pregnant patients, said lead author Luke Grosvenor, PhD, a research fellow with the Kaiser Permanente Division of Research.

“Based on this research, we would not say that gestational diabetes causes autism, or conclude that it is caused by other factors related to treatment of gestational diabetes, such as medication or lifestyle changes,” Grosvenor said. “But this study provides some important areas for future research, such as why there may be a difference in likelihood of autism by sex of the baby, and why we saw greater likelihood of developmental delays in girls if the mother had a milder version of metabolic disorder in early pregnancy.”

Of the total 4,546 mothers, 403 had gestational diabetes and 64 had elevated blood glucose levels but no diagnosis, which the researchers defined as sub-clinical impaired glucose tolerance (IGT). Of the children, 683 had an autism spectrum disorder diagnosis, and 2,054 had a developmental delay diagnosis. These children were compared to 1,809 children who did not have either diagnosis. All the children were born between 2011 and 2018 and followed through 2023.

The analysis found the strongest link between early gestational diabetes and autism in both genders. It also found a strong association between impaired glucose tolerance and developmental delays in girls.

The study also identified an increased likelihood of developmental delay in girls whose mothers’ gestational diabetes was diagnosed late. However, this subgroup of children was relatively small, so further research is needed, the authors said.

While the findings might suggest more focus on diagnosing gestational diabetes in early pregnancy, the reality in practice is more complicated. Gestational diabetes screening usually takes place between 24 and 28 weeks gestation, and a positive screening can lead to major lifestyle changes in activity and diet, blood sugar monitoring several times a day, and potential use of medication.

Doctors weigh the burden of treating diabetes during pregnancy with any potential benefit in outcomes, such as avoiding pregnancy and birth complications. A growing body of research suggests that early gestational diabetes diagnosis (before 24 weeks) may not make a difference in infant outcomes such as large-for-gestational age baby, caesarean section, preterm birth, or NICU admission.

Some health systems, such as Kaiser Permanente Northern California, are reducing the emphasis on early screening for gestational diabetes (a condition that occurs only during pregnancy) and ensuring that patients at risk for chronic diabetes (a lifetime condition) are screened early in pregnancy. There are different medical tests for gestational diabetes and chronic (type 2) diabetes.

Blood sugar’s relationship to autism spectrum disorder and developmental delays adds another factor into the complex mix. If further research suggests early screening for metabolic disorders could make a difference in likelihood of autism, that would be another thing for doctors and patients to consider, said senior author Lisa Croen, PhD, a senior research scientist with the Division of Research.

“Blood sugar metabolism is an important area for future research in neurodevelopmental disorders, and I expect future research will provide greater insights to help guide treatment,” Croen said.

She noted that the potential causes of autism spectrum disorder are broad and complex, extending to genetics, environmental exposure, infections, fevers, and other maternal health conditions.

If future research supports the findings in this study, Grosvenor said, pregnant patients with mild glucose metabolism issues might benefit from lifestyle changes during pregnancy involving diet and movement.

The study was funded by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

Additional co-authors were Yinge Quan, PhD, Stacey Alexeeff, PhD, Yeyi Zhu, PhD, and Jennifer L. Ames, PhD, of the Division of Research; Erica P. Gunderson, PhD, MPH, of the Kaiser Permanente School of Medicine; Lauren A. Weiss, PhD, of the University of California, San Francisco; Elizabeth Sahagun, PhD, Paul Ashwood, PhD, and Judy Van de Water, PhD, of the University of California, Davis; and Robert Yolken, MD, of Johns Hopkins University.

###

About the Kaiser Permanente Division of Research

The Kaiser Permanente Division of Research conducts, publishes, and disseminates epidemiologic and health services research to improve the health and medical care of Kaiser Permanente members and society at large. KPDOR seeks to understand the determinants of illness and well-being and to improve the quality and cost-effectiveness of health care. Currently, DOR’s 720-plus staff, including 73 research and staff scientists, are working on nearly 630 epidemiological and health services research projects. For more information, visit divisionofresearch.kp.org or follow us @KPDOR.

Comments (0)