Kaiser Permanente study shows the benefit of identifying and treating patients with H. pylori

People treated for Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) — a type of bacteria that infects the stomach — have a much lower risk of developing stomach cancer than people who have H. pylori but do not get treated, new Kaiser Permanente research shows.

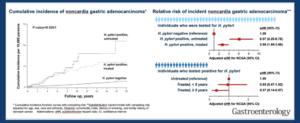

The retrospective study found that people infected with H. pylori who underwent treatment had a 63% lower risk of developing stomach cancer than those who were infected but did not get treated. The effect of treatment on cancer risk reduction was clearly evident after 8 years of follow-up.

“It takes time for the inflammation H. pylori causes in the stomach to progress to precancerous conditions, and then to cancer,” said lead author Dan Li, MD, an adjunct investigator with the Kaiser Permanente Division of Research and a gastroenterologist with The Permanente Medical Group. So, there is a lag time before you begin to see the clear difference between those who are treated and those who are not.”

The study, published May 2 in Gastroenterology, included 716,567 Kaiser Permanente Northern California (KPNC) members tested for H. pylori between 1997 and 2015. It is the first large community-based study in the U.S. to assess the effect of H. pylori treatment on stomach cancer incidence. Most large studies on H. pylori and stomach cancer have been conducted in Asia.

“Because studies regarding the potential benefits of treating H. pylori were in countries with differences in diet and other risk factors, this study helps inform care for our patients in the U.S.,” said Douglas Corley, MD, PhD, MPH, a DOR senior research scientist and a TPMG gastroenterologist.

“H. pylori is one of the most common causes of stomach cancer,” Corley added. “Having evidence that treating it decreases risk, even after being infected for many years, is a powerful tool — like knowing that stopping smoking will decrease your risk of lung cancer, even if you have been a smoker for many years.”

H. pylori was discovered in 1984 by researchers studying patients with gastritis — inflammation of the stomach lining. About 30% of people in the U.S. are infected with H. pylori; in other parts of the world, the number is as high as 50% to 70%. People usually contract the bacteria during infancy or early childhood.

If untreated, H. pylori can cause chronic inflammation of the stomach lining. This inflammation may gradually cause precancerous changes or even cancer. To kill the bacteria, patients take medications, such as antibiotics and proton pump inhibitors, for 10-14 days.

The American Cancer Society estimates that 26,500 new cases of stomach cancer will be diagnosed in the U.S. in 2023, with rates varying substantially by race and ethnicity. H. pylori is the number one risk factor for stomach cancer — it is responsible for about 90% of these cancers. Yet, many people who are infected with the bacteria will never develop stomach cancer.

We need studies to determine the optimal strategy for screening for and treating H. pylori in the general population, and in particular, how to effectively screen and treat H. pylori in higher-risk populations in the U.S.

— Dan Li, MD

The study found that people who were treated for the bacteria still had a higher risk of developing stomach cancer than people who had never had H. pylori. This is likely because many people with chronic H. pylori infection already developed some precancerous changes in their stomach which led to an increased risk even after H. pylori treatment. This finding suggests that H. pylori ideally should be treated before any precancerous changes develop.

The study also found that people treated for H. pylori had a much lower risk of developing stomach cancer than the general population of KPNC patients. “This is important because there is no routine screening for H. pylori, we know that in the general population there are many people who have it but don’t know it and don’t get treated,” said Li. “This part of our analysis provides further evidence that testing for H. pylori and treatment can reduce stomach cancer incidence among infected people.”

The researchers took multiple steps to clearly identify which patients had the bacteria and were treated. They began by separating the patients whose H. pylori test showed active infection on a breath test, stool test, or stomach biopsy from those who had a positive blood test, which can detect antibodies but cannot distinguish a current infection from a prior infection. Next, they identified which patients had been treated for H. pylori and which had not.

The researchers took multiple steps to clearly identify which patients had the bacteria and were treated. They began by separating the patients whose H. pylori test showed active infection on a breath test, stool test, or stomach biopsy from those who had a positive blood test, which can detect antibodies but cannot distinguish a current infection from a prior infection. Next, they identified which patients had been treated for H. pylori and which had not.

The research team also looked to see which treated patients had a follow-up test confirming the bacteria was gone. Then, they used KPNC’s Cancer Registry to identify patients who had been diagnosed with stomach cancer through December 2018. They focused on non-cardia stomach cancer, which occurs in the mid- to lower- part of the stomach and is the main type of stomach cancer caused by chronic H. pylori infection.

“In the U.S., there is a 2- to 3-fold higher incidence rate of stomach cancer among people who are Asian, Black, Hispanic, or first-generation immigrants from the high incidence areas in the world, such as East Asia and parts of South America,” said Li. “We need studies to determine the optimal strategy for screening for and treating H. pylori in the general population, and in particular, how to effectively screen and treat H. pylori in higher-risk populations in the U.S.”

The study was funded by the Kaiser Permanente Northern California Community Health Research Grants Program, The Permanente Medical Group Delivery Science & Applied Research Program, and The Permanente Medical Group.

Co-authors include Sheng-Fang Jiang, MS, of the Kaiser Permanente Division of Research; Nan Ye Lei, DO, of The Permanente Medical Group; and Shailja C. Shah, MD, MPH, of the University of California, San Diego.

# # #

About the Kaiser Permanente Division of Research

The Kaiser Permanente Division of Research conducts, publishes and disseminates epidemiologic and health services research to improve the health and medical care of Kaiser Permanente members and society at large. It seeks to understand the determinants of illness and well-being, and to improve the quality and cost-effectiveness of health care. Currently, DOR’s 600-plus staff is working on more than 450 epidemiological and health services research projects. For more information, visit divisionofresearch.kaiserpermanente.org or follow us @KPDOR.

Comments (0)